Welcome to OK, Perfect

Some thoughts on material culture, the act of noticing, and an anthropomorphic juice carton

Hello, friends and readers!

Welcome to Ok, Perfect — a new newsletter about material culture and my personal affinity for the weird little designed objects that punctuate our lives. And as I’ve come to realize as I prepare the first few posts and interviews, it is also, above all, a project about noticing and looking.

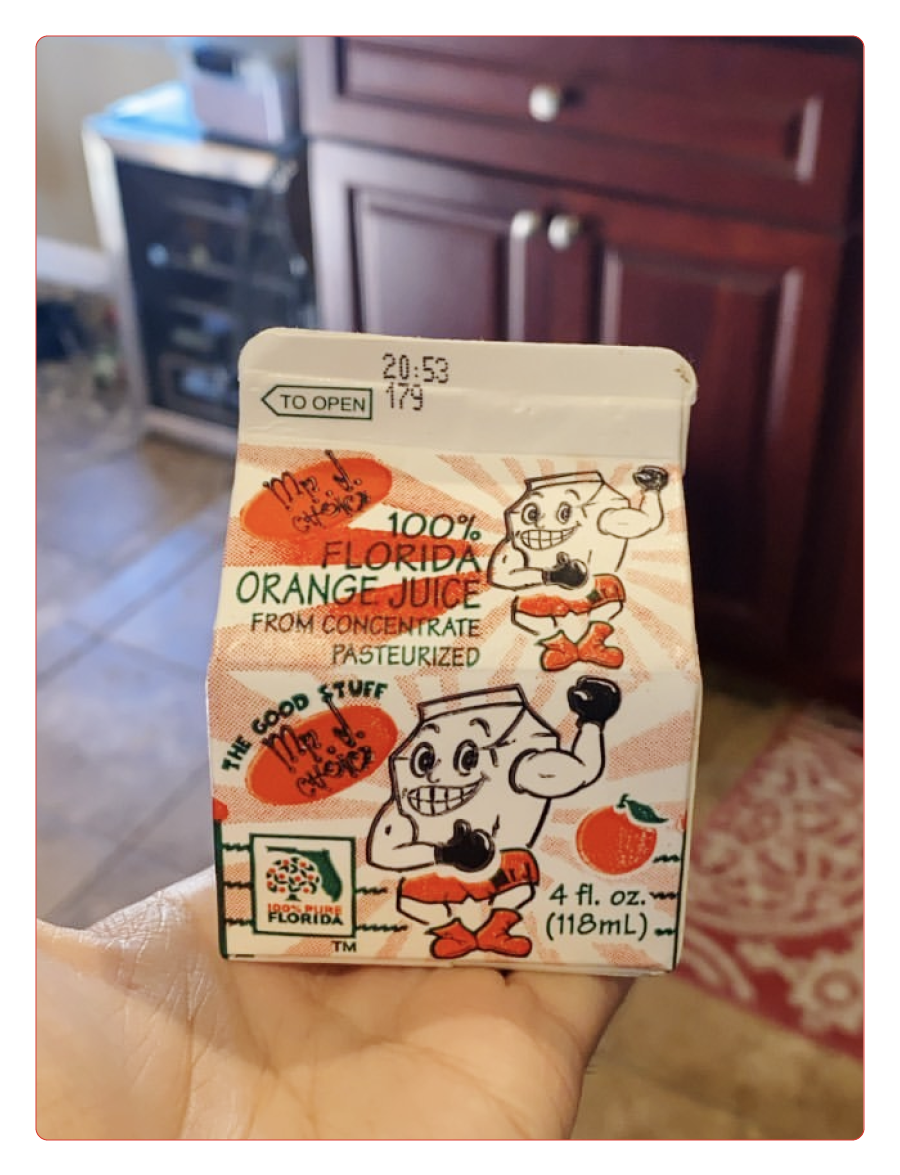

A few years ago, I started posting pictures of objects on my Instagram story with the phrase “Perfect Design.” It started out with a miniature kids-sized carton of orange juice, salvaged by my sister-in-law from the lunchroom at the elementary school where she works and tucked into the corner of my brother’s fridge. It was small enough to fit in the palm of my hand, adorned with a variety of typographic choices and not one, but two illustrations of an anthropomorphic juice carton named “Mr. J.” Mr. J. has bulging biceps and appears to be wearing boxing gloves (confirmed, via a photo of the other Mr. J All-in-One Calcium Fortified Juice Products that includes a flavor called T.K.O. Fruit Punch — get it?).

The juice carton was goofy, absurd, and decidedly fucked up — and it delighted me in every way. From the slightly-misaligned 3-color flexographic print, to the tiny dots making up the Floridian sunrays, to Mr. J.’s shit-eating grin, everything about it was appealing to me. Even the familiar form of the waxy cardboard carton felt charming in this miniaturized version, like an American Girl doll went to Costco and bought a thing of OJ for brunch with the rest of the dolls. Call it “folk design” or “mundane design,” — for me, there was no other word for it but perfect.

Mr. J and his busted smile kickstarted my minor obsession with documenting the off-the-wall designed objects I came across in the wild. Over the next two and a half years, I occasionally updated a highlight on my Instagram with other examples of Perfect Design that crossed my path: a pastoral landscape printed on a stick of pale yellow butter; a construction-paper-cutout sign for a Park Slope nursery school that sold Christmas trees; a handpainted farm sign in Connecticut. They ranged from the highbrow (the opening credits to Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday) to the lowbrow (the neon hot dog sign for Nathan’s on the Coney Island boardwalk). There was the occasional trendy branded item (a can of lime flavored Bawi agua fresca), but most objects would not necessarily find themselves in the pantheon of design history (a Waffle House clock with various menu items elegantly placed in the center).

That’s kind of the point. In an industry prone to slickness and optimization, even the most playful work from the top design firms had to go through a round of revision with Gavin and Kelsey from Marketing. And while I do love the satisfying perfect-fit cohesion of a good brand system (it is my literal job) — the kind of design I enjoy most isn’t made by Pentagram or anyone who has a Young Guns. In fact, the omnipresence of the digital in today’s creative industries, where we are quite literally expected to make things pixel perfect, has only drawn me closer to the comfort and contentment of a designed object I can hold in my hand (or, at the very least, something I can touch and feel or otherwise see existing in three dimensions in front of me). There are at least four typefaces used on a carton of Mr. J, and I wouldn’t necessarily use any of them in my own work. And yet as a whole, I find it more compelling than any dumb subway ad trying to get my attention. The design of the objects I find might not even be good by industry standards, but it is perfect — which is to say, imperfect, idiosyncratic, and full of human feeling.

I am very obviously not the only designer who feels this way. In a recent column for It’s Nice That, editor-at-large Elizabeth Goodspeed (who also writes a great newsletter about design ephemera) calls us all out:

I’m aware that being a graphic designer who loves signage, especially “folk” signage – as in, signs created by individuals without formal design training – is incredibly cliché. When a graphic designer I follow goes on a trip upstate, I can almost guarantee that within a day they’ll post a picture online of a sign from a bait and tackle shop or small-town diner.

She got our asses, you guys. She goes on to extrapolate why we do this:

But of course we’re drawn to signs! It’s a natural reflex for designers to celebrate any instance of graphic design in the wild. In a field that can be relatively insular, signage is a reminder that design exists outside our screens.

To me, this reflex is less of an impulse to celebrate design, as a discipline, but rather to celebrate the actual act of noticing something, of looking on purpose at the materials, textures, letters, words, shapes, and colors that make up the world around us. Much of that world is completely unconcerned with screens and formal design training, which makes it all the more compelling.

Yisel Garcia, an artist and friend I interviewed for this project, embodies this practice in her daily life. She frequently takes and posts photos of objects that she sees on her walks. Over the years, certain motifs have appeared repeatedly: donut boxes, dew drops, springs, yellow pencils. She explains her relationship to noticing them:

I see all these objects as pockets into a feeling of hope, or little windows into relating to something differently, a little spark that’s moving me or propelling me in this new direction.

When I first came up with the idea for this newsletter, I envisioned it as a place where I could share the “instances of graphic design in the wild,” as Goodspeed called the practice. (I deleted Instagram from my phone a few months ago, so I currently have nowhere to share the things I see.) I’d invite other designers to do the same, I imagined. But after speaking to Yisel (in a conversation that I’ll share in a later post), I realized that above all, I want this to be a project about looking, seeing, and noticing the material culture all around us, in real life.

This solved a major problem with my initial concept. I worried, at first, that taking any design or object out of context and plopping it in a newsletter would rip meaning from it, disembody it in the same way that Pinterest or Instagram can strip artists of credit and flatten their work into a replicable aesthetic. After speaking to Yisel, I realized: when we look at the world — the real, offline, tangible world — we become the context for the things we notice. It is less about the capital-lettered Design History than it is about the history of each of us: the things we notice, the items we collect, the material culture that surrounds us in our daily lives. For me, it’s wacky graphic design ephemera, hand-painted signs, anything with type. For Yisel, it’s often objects distilled to their simplest form. For you, it’s something else entirely. Examining someone else’s Perfect Design is kind of like looking through their trash. It tells us something we didn’t even know to ask.

I’ll send out this newsletter every week, when I can. There will be occasional interviews with designers, creatives, and people who like to notice things. There will also be trips into the archives of my camera roll, deep dives into design ephemera in pop culture, and, hopefully, Perfect Designs of the Month. I took most of the photos from a distance, with my phone, often from a moving vehicle, so there will be no sheen of professionalism here — but I do think it will be fun. Let’s just see where this thing rolls, ok? Ok.

Suze

Thank you so much for including me in this absolutely wonderful essay! I couldn't agree more about the act of noticing being the most important thing (etc.)—can't wait to read more <3

more food clocks PLEASE